Stories

Insights & Ideas

We’re always learning and expanding our thinking.

Reshaping My Studio

Supportive Environments for a New Year, Part 1

Resolutions and intentions are easy to make but hard to convert into action and change. So, I’m starting the year off by going back to basics which, as an environmental psychologist and artist, means taking a hard look at my studio environment and pondering how I can get it to better support me in doing the things I want to do.

Eighteen Small Experiments

I have just finished a year of small writing experiments and you, dear reader, were part of my laboratory. What are small experiments and what can they teach us? My own experiments have been instrumental in helping me incrementally find my way in the world of blog writing.

Ushering in a New Decade of Awe and Wonder

As I head into this next decade of my life, I am reminded of the powerful physical, mental, and creative benefits of taking the time to invite in everyday moments of awe and wonder.

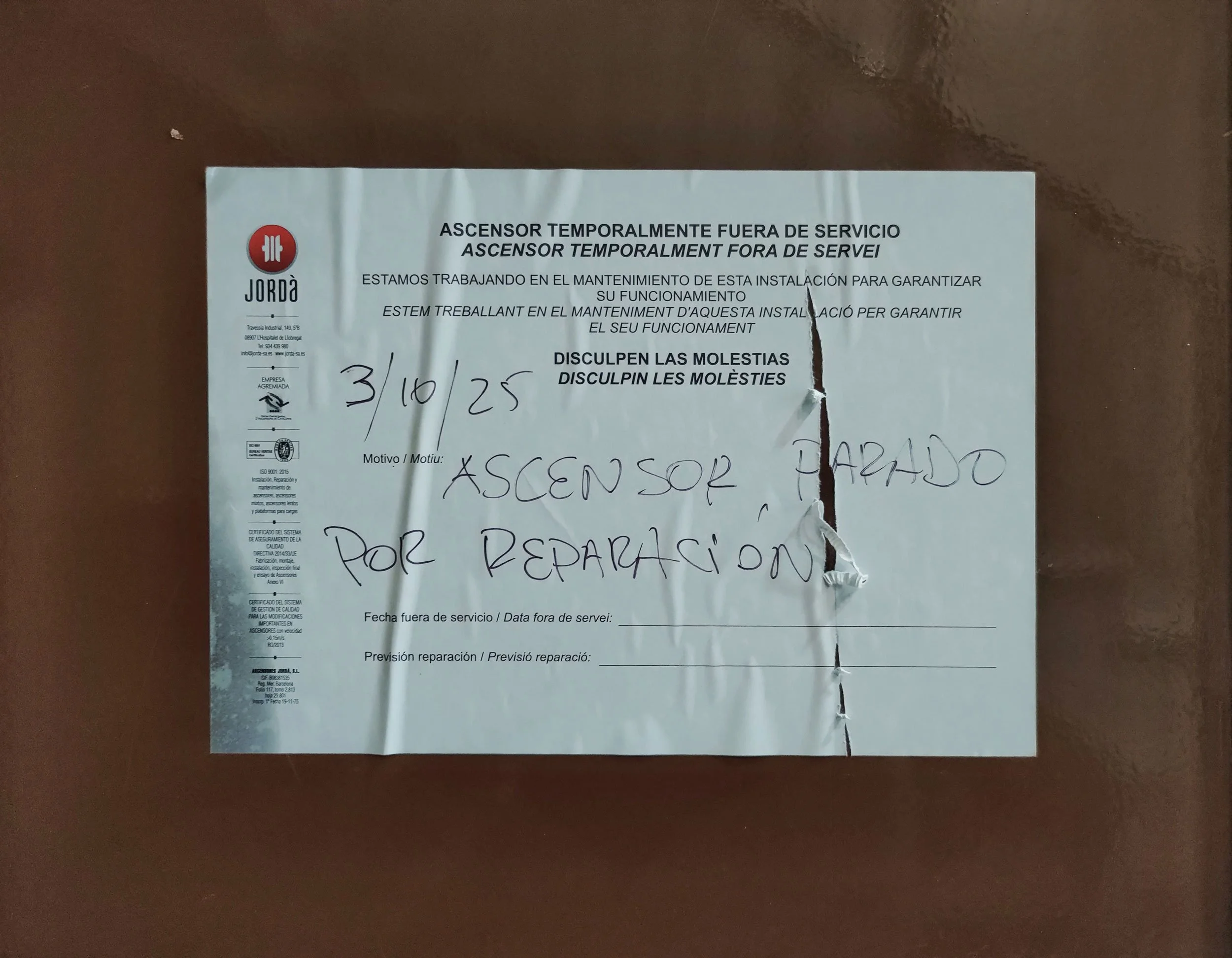

Understanding Is Good Medicine – What We Can Learn From Barcelona’s Hospital Sant Pau

Understanding is good medicine. When we know what’s going on we are less stressed, less likely to become mentally fatigued, and better able to make decisions. Our brains are generally good at building the mental maps that support understanding, but it helps immensely if the environment or information itself is organized to make map-making easier. What does this look like?

Using the SEE Framework for Creative Community Engagement

Meredith King, one of reDirect’s 2025 fellows, shares how the SEE framework shaped her project with Ann Arbor’s Office of Sustainability and Innovations (OSI). She created a community engagement guide to help staff turn a mobile nanogrid into a learning lab to help citizens take steps toward more sustainable living.

Why I Need More Help Than I Thought

As my hair has gotten greyer, my instinct toward self-reliance has only gotten stronger. But lately I’ve been contemplating the missed opportunities – for others as well as ourselves – when we fail to recognize the many ways that helping helps.

The Opposite of Talking

The ping-pong conversational style of information sharing and anecdote exchange seems to dominate my conversations these days. And while there’s nothing particularly wrong with this, these conversations often leave me wanting more. Is our need to share drowning out our need to be understood and to understand others? Is our default conversational style making us inadvertently miss out on opportunities for deeper connection and growth? How can we literally reframe the conversation?

How Creativity Blooms – the Hidden Power of Everyday Environments

In any kind of caregiving – whether for plants or our own creative selves – it is the cumulative effects of the environments experienced day in and out that impact us most. Good intentions are fine but having environments that support the creative process is what allows our creativity to blossom. What does creativity need and how can we create an environment that helps meet those needs?

Swimming in Uncomfortable Waters

Uncertainty brings its own kind of mental pain. And the temptation to avoid it – even when it is part of learning and discovery – can be hard to resist. Whether we cling to familiar shores out of a sense of self-preservation, love, or entitlement, we often end up limiting our own opportunities for learning, discovery, and personal growth. How can we change our environments or our own mindsets to support us while we swim in deeper waters?

Curiosity is a Superpower

People are designed to be curious just like greyhounds are designed to run. Both can probably still survive if those natural tendencies are caged, but they are unlikely to flourish. How does curiosity help us be our best selves? What can we do to free our curiosity if we find it has been caged through neglect, complacency, or an inhospitable environment?

Boredom Is Your Brain’s Way of Saying, “Let’s Go Explore!”

Just like the pain of hunger is a signal to feed our bodies, the pain of boredom is a signal to feed our brains. Boredom cries out for mental engagement but it doesn’t tell us how or with what. The big businesses of the attention economy are more than happy to provide quick and easy short term boredom balms, but these rarely enrich us. How can we learn to listen to our boredom and reach for something that is more nourishing in the long run?

The Magic of Being On The Edge

The pleasurable state of mind between the known and the unknown, between familiarity and exploration, is where creativity flourishes and discoveries are made. How can you cultivate this state of mind and what can it do for you?